Forging bonds across the dividing lines of race, class, and age helps me expand my self-image and my connection to the world around me. It frees me from society's narrow definition of who I have been groomed to be and which people I can relate to. Connecting to people who have had radically different life experiences helps me to transcend the limits of my little physical existence.

A recent analysis of diversity research by Dr. Katherine W. Phillips from the Columbia Business School confirms my experience. According to various studies, when diverse people come together to do work, they are more effective at their task than a homogeneous group. For example, it turns out that diverse juries are more diligent in their deliberation of the case. Dissent from a person who is different from us provokes a more thoughtful response than dissent from someone we see as a peer. Diverse research teams produce more robust research that is more widely cited than that of homogeneous research teams. From the article:

Members of a homogeneous group rest somewhat assured that they will agree with one another; that they will understand one another's perspectives and beliefs; that they will be able to easily come to a consensus. But when members of a group notice that they are socially different from one another, they change their expectations. They anticipate differences of opinion and perspective. They assume they will need to work harder to come to a consensus. This logic helps to explain both the upside and the downside of social diversity: people work harder in diverse environments both cognitively and socially. They might not like it, but the hard work can lead to better outcomes.

Elated by this confirmation of my own life experience, I began to think about other implications of this research. I wondered if the benefits of diverse working groups could be flipped on its head: if diversity can increase the quality of group work beyond what any of the individual members are capable of, could homogeneity spur the regression of a group to a level below that of any of the individuals?

In other words, does a homogeneous group create a sort of Nega-Voltron, whose whole is worse than the sum of the parts?

For example, I have been in situations in which I participated in an activity that I was firmly against, morally, and yet I didn't speak out (let alone act out) in defiance of the crowd.

When I'm walking down the street with other heterosexual men and we pass a woman, I often hear an internal voice telling me to make a comment, gesture, or facial expression to show my judgment of how physically attractive the woman is.

It doesn't matter how enlightened my guys are. The urge to pass judgment on a woman's body operates independently of the individuals that I'm with. It's been absorbed into me since birth, thanks to the spoken and unspoken societal rules that entitle men like me to a sense of dominion over women in public spaces. In this moment among guys, I fear that if I don't play a part in judging the passing woman, I will be mocked, insulted, or shunned by my peers.

And sometimes I've acted on this peer pressure, making unsolicited comments or nudging my buddies in the side. Deep down, I know that this judgment of body (independent of the woman's personality) is wrong and does violence to both myself and the woman.

Given the type of men I usually hang out with, my buddy probably doesn't want to participate in this judgment of the woman either! And yet there we are, joining up to form the Nega-Voltron of patriarchal dominion, taking action that, deep down, neither of us really wants to do.

Men like me have mothers, sisters, female partners, daughters, and female friends. What if, in my moment of slipping into that easy stream of judgment of a woman's physical features, I could be whisked away to an isolation chamber that exists outside of time and space, and under the hot lights, be forced to ask myself:

This is not an example of diversity helping to create progress. This is diversity preventing oppression from coming to life through me. It's the grim, unglamorous, utilitarian side of diversity's benefits.

Judgment of women on the street is one of the most common and widely accepted forms of oppression in America. But the implications of this diversity research go beyond catcalling. It's worth taking a deep breath and facing a different kind of state-backed American street oppression.

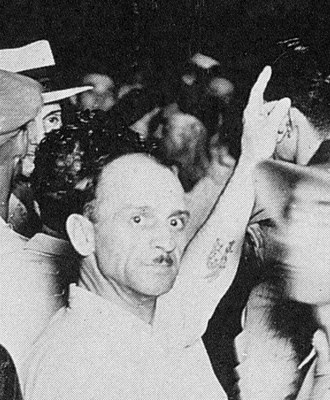

As a White person, I've been trained to forget about these moments in American history. But we White people can learn by consciously choosing not to forget.

I look at the picture of genocidal White madness above and try to see this mob as a group of distinct individuals. What happens when we zoom in on one of these murderers?

Is it possible that behind this satisfied grimace, this man knows he has joined the ranks of the worst that humanity has to offer? If we could put him in the isolation room, beyond space and time, with the hot lights glaring, and watch him ask himself:

Do I wish to pass on a world to my children and grandchildren in which a human being can be murdered with impunity, even joy, by a state-sanctioned mob?

I don't propose exploring the mentality of the oppressor merely out of an academic interest. I propose this exploration because in it may lie a way to prevent humanity's worst moments yet to come.

I propose that our experience with diversity can disrupt our internal oppressive programming in the same way Scout's words disrupt the momentum of the lynch mob. Just as being with diverse people and having shared work to reframe our own ways of approaching the world as just one among many, I propose that diversity also holds people of privilege back from dipping back into the easy streams of oppression (from microaggressions to murder) that have been built into the fabric of America since Columbus set foot on Hispaniola.

Friends are not the same as working groups, of course. But that doesn't preclude wondering: does Darren Wilson have any close Black friends? We White Americans are relentlessly trained to fear Black people, and on an individual level, that psychological training can best be undone through interpersonal connections across the racial divide--connections that push us to form new, diverse Voltrons with people from a wide variety of life experiences and backgrounds.

So if Wilson doesn't have any close Black friends (and thus is used to operating as part of a homogeneous, White Voltron), could that have affected his decision to pull the trigger, again and again and again, on Michael Brown, a young, unarmed Black man?

The future of our country depends largely on a massive shift in White consciousness and action. We must meet our brown-skinned brothers and sisters at the table to transcend our White supremacist legacy. It will require us to take a long, hard look at not just our past, but also our mirror of today. When we come together in honesty and humility across the racial divide, we will foster a racial reconciliation that would be the first of its kind in human history.

Imagine if Black, Brown, and White Americans could all wake up in the morning and rise knowing that their lives are protected and valued equally. In forming that Voltron, what obstacle could America not overcome?

#ferguson #handsupdontshoot #blacklivesmatter #blacklifematters #fergusonoctober

RSS Feed

RSS Feed